The Fisk University Jubilee Quartet in 1909, from left: Alfred G. King (first bass), James A. Myers (second tenor), Noah W. Ryder (second bass) and John W. Work II (first tenor).

Courtesy of Doug Seroff (Listen here)

Abbott, Lynn, and Doug Seroff. To Do This, You Must Know How: Music Pedagogy in the Black Gospel Quartet Tradition. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2013.

The authors discuss how the jubilee quartet tradition emanated from the revival of university-based vocal harmony singing, most notably the Fisk Jubilee Quartet and its leader, John Work II. They further examine the mining camps of Birmingham and Bessemer, Alabama, and on to Chicago and New Orleans. Early in the twentieth century there were countless initiatives in support of African American vocal music training conducted on both national and local levels. Later, singers such as Silas Steele added the pulpit zeal of the Baptist preacher to jubilee quartet, opening the door for the hard gospel quartet style that dominated the 1950s and 1960s.

to Fisk University and the Jubilee Singers, this article discusses the early history of the Cotton Blossom Singers at Piney Woods Country Life School in Mississippi from about 1921 to the 1940s. Locally, the group was known as the Piney Woods Singers. Their travels, repertoire, radio programs, and their encounters with racism are discussed. A day-by-day account in one week of travel is included. (Author’s abstract, slightly revised)

to Fisk University and the Jubilee Singers, this article discusses the early history of the Cotton Blossom Singers at Piney Woods Country Life School in Mississippi from about 1921 to the 1940s. Locally, the group was known as the Piney Woods Singers. Their travels, repertoire, radio programs, and their encounters with racism are discussed. A day-by-day account in one week of travel is included. (Author’s abstract, slightly revised) Spearman, Rawn Wardell. “The ‘Joy’ of Langston Hughes and Howard Swanson.” Black Perspective in Music 9, no. 2 (1981): 121–38.

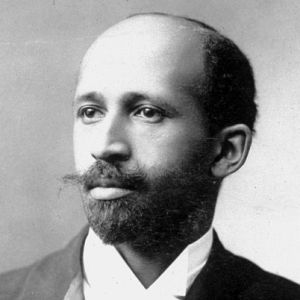

Spearman, Rawn Wardell. “The ‘Joy’ of Langston Hughes and Howard Swanson.” Black Perspective in Music 9, no. 2 (1981): 121–38. Scholar and activist W.E.B. Du Bois

Scholar and activist W.E.B. Du Bois