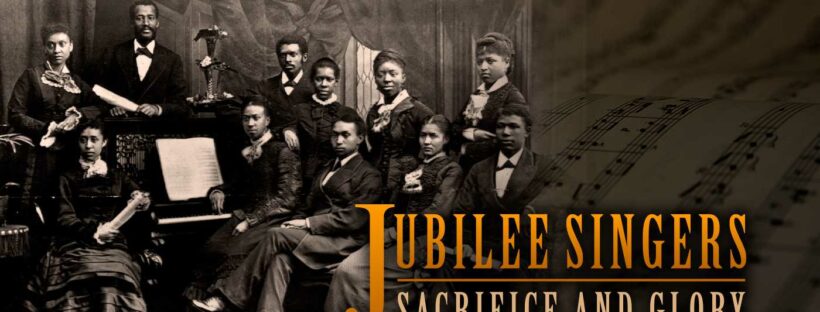

The profound and inspiring story of students who battled prejudice and oppression to sing their way into the nation’s heart.

On November 16, 1871, a group of unknown singers — all but two of them former slaves and many of them still in their teens — arrived at Oberlin College in Ohio to perform before a national convention of influential ministers. After a few standard ballads, the chorus began to sing spirituals — “Steal Away” and other songs” associated with slavery and the dark past, sacred to our parents,” as soprano Ella Sheppard recalled. It was one of the first public performances of the secret music African Americans had sung in fields and behind closed doors. More